Hi everybody, This is the iconic case study of ITC & How ITC helps Indian farmers

every now and then we keep hearing about the pathetic state of farmers in our Country.

And in spite of employing more than 50% of the workforce, the condition of the Indian

the agricultural sector has been so bad that every day 28 people dependent on agriculture commit Suicide.

And every time we hear this news 99% of us curse the government, we feel sorry for the

farmers and we just move on until another news comes in.

And in this process of shallow activism, we never ever try to understand what exactly

is the problem of the farmers on the ground.

But you know what, guys, while every single media house and politician have been using

the state of farmers for their own advantage, the Indian tobacco company has been working

on a revolutionary business strategy, and has improved the lives of 4 million farmers across 35,000 villages in India.

And the best part is that they have achieved this not by doing charity, but by deploying

a world-class business strategy that has even doubled the income of farmers.

And if you understand the strategy properly, you will not just be able to tap into a million

dollar business opportunity in the Indian agricultural space.

But you’ll also be able to understand how can companies like zomato and Grofers become

profitable in the next five to 10 years?

So the golden question is, what exactly is this strategy?

How will it help zomato and Grofers become profitable, and more importantly, what are

the business lessons that we need to learn from this wonderful case study?

This is a story that dates back to 1999 when the agricultural export division of ITC was not performing well at all.

During that time, soybean was a primary export commodity of ITC, and in 1999 4 million tonnes

of soybean or 80% of the produced soybean produced of India came from rural Madhya Pradesh.

80% of this produce was turned into soya meal that was used in poultry and cattle feed.

And eventually, ITC exported soya milk to countries such as China, Pakistan, Bangladesh and the even United Arab Emirates.

And the remaining 20% became edible oil, which again was a highly nutritional high demand Product.

So the soybean industry overall was supposed to be very, very profitable.

And the farmers who produced soybean was supposed to be extremely rich.

But guess what?

The soybean farmers in Madhya Pradesh were leading a miserable life, most of them struggling

in debt when they didn’t even have enough capital for the next season.

And at the same time, even companies like ITC that were procuring these crops were not able to make healthy profits.

So the question was when soybean was in such high demand in the international market, how

is it possible that neither the farmers nor the export companies were able to make healthy profits?

Well, as it turns out, it was because of a major inefficiency in the supply chain of soybeans.

And this is how it worked out.

APMC and Mandis of india

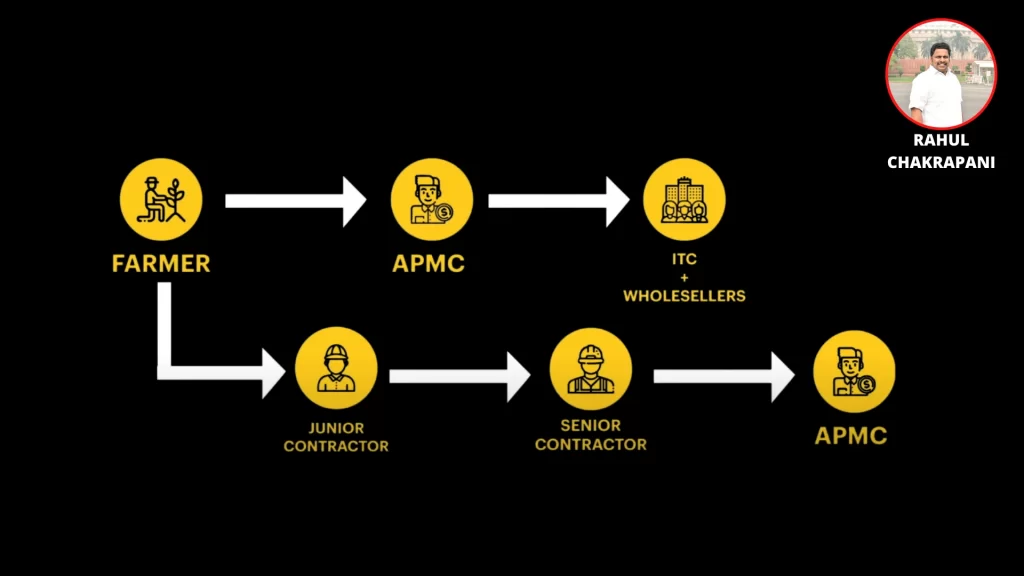

On paper, there were three elements in the supply chain, the farmers, the APMC or the

agricultural produce market committee, and then we had export companies like ITC and the wholesalers.

So ideally, the farmers were supposed to produce their crops and they were supposed to take it to the APMC

APMC was nothing but a body of licenced traders set up by the government to ensure that farmers

are not exploited by open trade. It’s also called the mandi.

So at of mandi, only government licenced traders could buy the produce from the farmers and no other trader was allowed.

So theoretically, these traders were supposed to auction for the crops and the highest

bidder procured the crops from the farmers.

This way, the farmers are supposed to get the best prices and they were supposed to be rich.

But in reality, this was far far away from the truth for three major reasons.

Firstly, the Mandis are about 30 to 50 kilometres far away from the farmers and more than 80%

of the farmers in our country are still small farmers.

So most of them either had storage facilities nor could they afford transportation facilities.

Therefore, they either had to rent a truck or they had to sell it to a junior contractor

who then sold it to the senior contractor, who then took it to the mandi.

So to put that straight, they either had to bear the cost of transportation or they had

to sell their produce to the middlemen at an extremely low cost.

Secondly, the farmers had no way to find out what exactly was a price being offered at

a particular mandi on a particular day.

As a result, they only had to rely on word of mouth and take the risk of travelling 50

kilometres with the hope that the word of mouth was true.

And lastly, since no other trader was allowed to procure crops from the mandi, the licenced

traders formed a cartel and instead of the auction for the highest price, they all quoted the

the same price which was way below the standard price of the produce.

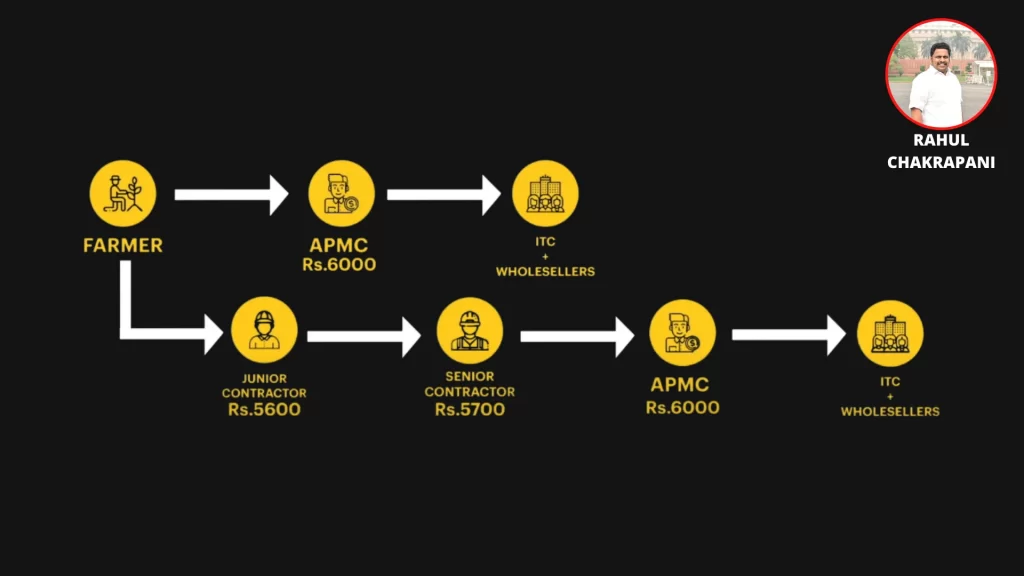

For example, if one quintal of soybean was supposed to be sold at a base price of 8000

rupees giving the farmer a profit of 2500 rupees per quintal, what the traders would

do is all of them would quote a price of 6000 rupees only. Why?

Because 1700 farmers have already travelled 50 kilometres and they cannot go back and

they couldn’t sell their products anywhere else.

So the farmer had no other option but to sell his crops at a bare minimum profit of 500

rupees to the licenced traders.

And worst case, if the farmer sold it to the junior contractor, then the profits would

go down further from 500 rupees to less than 100 rupees to sometimes even at a loss.

And to make matters worse, even after dragging the price down to a mere 500 rupees.

The mandi traders did not pay the farmers right away, and they took the hard on produce at an unofficial credit

and paid the farmers only when they made a profit.

And this time of credit would range between one week to even one month.

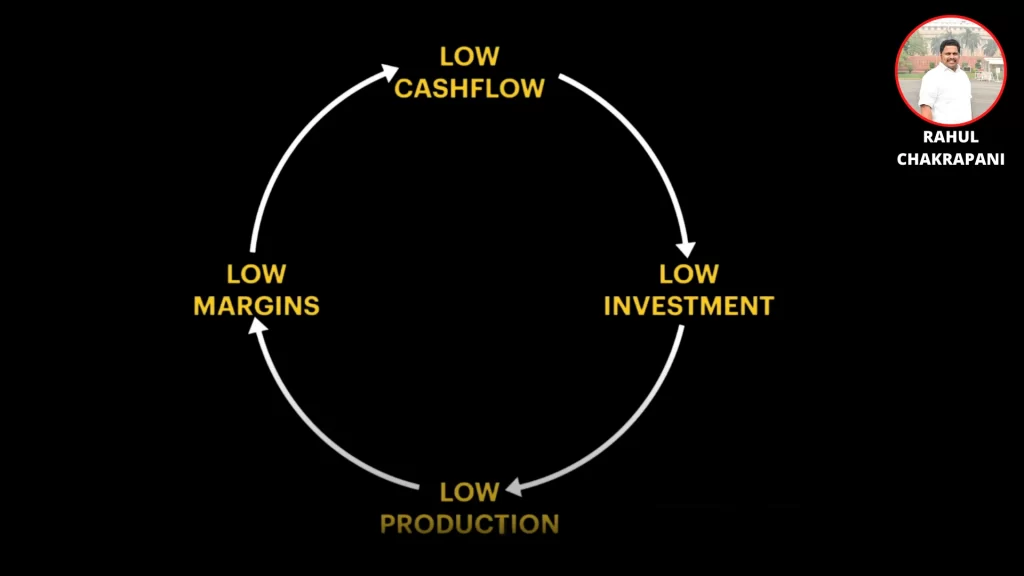

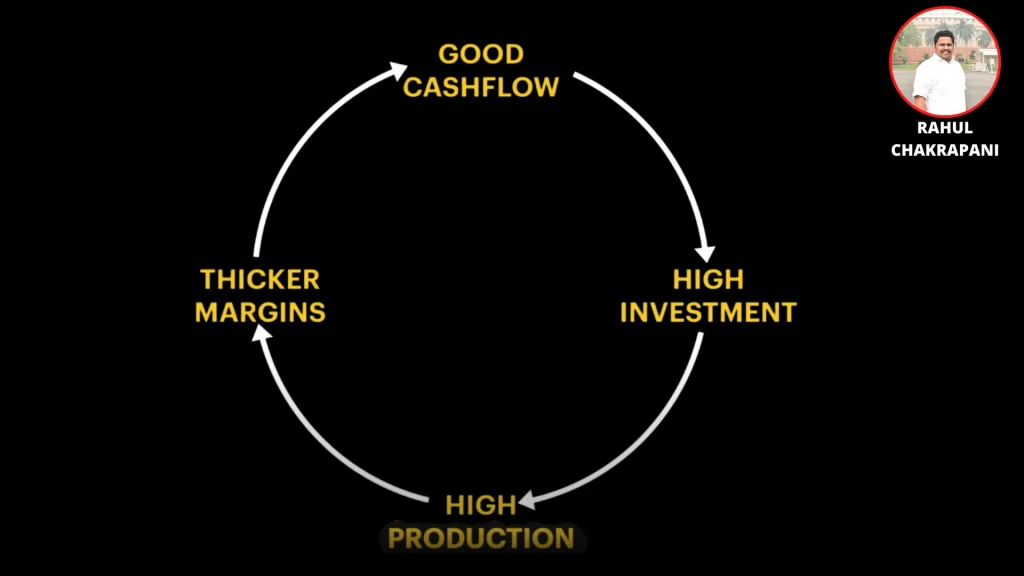

And this pathetic system put the farmers in a very very dangerous vicious cycle.

Since the farmers did not have enough cash flow.

It led to low investment into farming equipment and other essential inputs like pesticides and fertilisers.

This led to low production leading to low margins, which again led to a cash crunch.

In fact, even today, this is the state of most of the farmers in our country.

And at the end of the day, in 1999, the farmers were losing 60 to 70% of the potential value

of their crop with the agricultural gains of only 25 to 30% of the global standards.

But you know what, guys, this is when ITC came out with a

E-chaupal by ITC

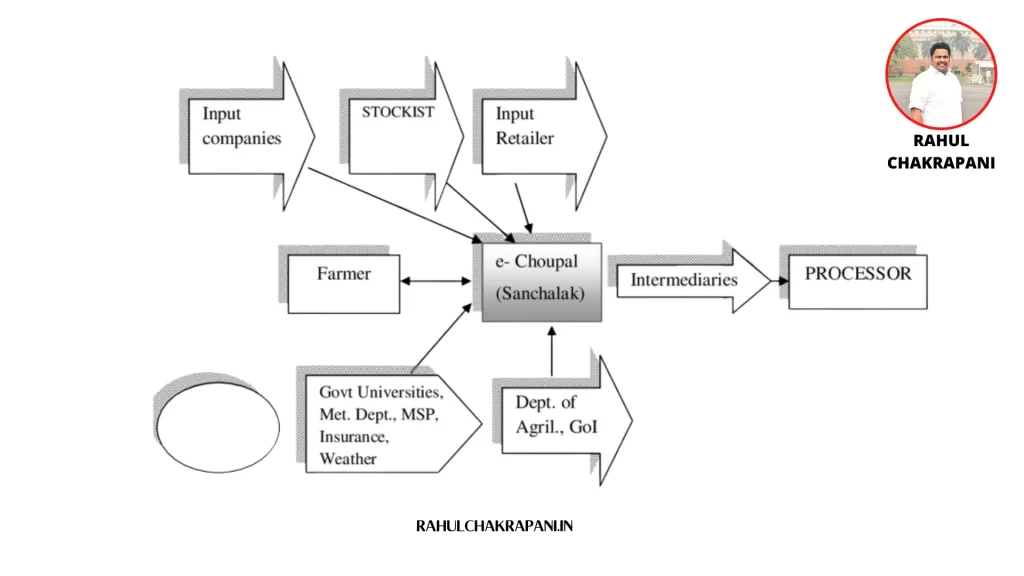

the revolutionary initiative was called the E-chaupal initiative and they installed

a super amazing tool called the computer in

the remotest villages of India in 1999 itself.

And under this initiative, ITC supplied a Windows PC and internet connection and a dot

matrix printer to all the village centres in its canopy.

To take this forward, they launched a website called soyachaupal.com, which consisted of

three of the most important information tabs needed for the farmers, data and weather reports

to help the farmers decide what is the best time to sow his seeds and to prevent him from

sowing seeds at the wrong time.

Number two was the best practices section.

For example, 18-inch spacing was considered to be the best practice.

However, many farmers were spacing the seed rows nine inches apart, which eventually resulted

in fewer yields.

And thirdly,

they had the Market Information section that gave the important market metrics,

including the daily price and volume traded at the Mandis and the ITC centres.

And this was supported by other important pages like the q&a section, the new section

and even the crop Information section.

Secondly,

they appointed a lead farmer called the Sanchalak who was responsible for helping

the farmers out with a computer operation.

And he was given a commission of 0.5% on the basis of the farmer’s productivity.

So because of the incentive, he automatically worked hard to help the farmers out with the

computer operation and to enable them to improve their productivity.

And thirdly,

ITC convinced the government to allow the company to procure the produce

directly from the farmers with the promise that they will provide reasonable cost and

will build an efficient and profitable supply chain.

PROBLEMS OF FARMERS IN INDIA

And that is all Ladies and gentlemen, the implementation of the E-chaupal began in 1999.

Back then ITC had five processing units in Madhya Pradesh and 39 warehouses making a

total of 44 touchpoints, covering 80% of the farmers in Madhya Pradesh, to which the

farmers could bring the soybean production.

The best part was that these points were only 20 to 30 kilometres away from the farmers

as compared to the 30 to a 50-kilometre range of the Mandis.

And this amazing setup ladies and gentlemen changed the way the farmers of Madhya Pradesh traded soybeans.

And this is how the system worked out.

First of all, the farmers were given all the important information through the E-chaupal

computers, which included everything from weather forecasts all the way up to the seed

sowing techniques.

Therefore, the farmers were confidently able to invest in their crops.

This reduced the risk of spoiled crops and at the same time, it increased the yield.

Then after the harvesting was done, they could directly have a look at the website to see

how much price was being offered at the Apmc and the ITC centre on a daily basis?

Eventually, they could compare the prices and then decide where to go to have higher profits.

In this case, ITC even reimburse the transportation cost to the farmers because of which, they

do not have to depend on the contractors to sell their yield at a bare minimum profit.

After that, when they arrived at the ITC centre, the processing facility also included a soil testing lab.

And here’s where top great scientists offered the best recommendation for fertilisers or

additives based on the chemical composition of the farmer’s soil sample.

And lastly, the farmer was given cash on delivery for the sale of his products immediately and

this was a very big deal because it enables him to buy fertiliser and other essential

products that were needed for the next season.

ECNOMIC SYSTEM

And this wonderful system, ladies and gentlemen, turn the disastrous, vicious cycle into a

virtuous cycle by which the farmers had good cash flow, which led to high investment into

farming equipment that led to high productivity, eventually giving them thicker margins and

better cash flow.

On top of that, in spite of all these reimbursements,

this setup was so amazing that even ITC ended up saving $3 per tonne on transportation,

and at the same time, the farmers are able to earn $8 extra per tonne.

Furthermore, this move turned out to be extremely profitable for ITC, because they got the raw material

from the farmers at a low cost And we’re able to use that for their FMCG division.

And today, each E-chaupal initiative already has become the largest initiative among the

internet-based interventions in rural India, reaching out to more than 4 million farmers

across 35,000 villages in 10 different states.

And today, these crops include soya bean, coffee, wheat, rice, pulses, and even shrimp.

This is the incredible story of the E-chaupal initiative.

And this brings me to the most important part of the episode and that are the lessons from

the case study and the business opportunities arising in the Indian agricultural space.

Before we move on, I want to thank our wonderful partners for today’s episode and that is going dutch.

People just like the farmers were stuck in a dangerous vicious cycle because of not having

enough cash flow.

Have you realised that knowingly or unknowingly even we are stuck in a vicious cycle because

of not tracking our expenses, because if you don’t know how much you will be spending,

you don’t know how much you will save.

And if you cannot project your savings, you cannot make strategic investment decisions.

And eventually, this little complacency ends up costing us a lot of money in the future.

That’s way before they sponsored us. And you know what, guys,

I have used many expense management apps in the past three years.

LESSONS FROM ITC

Moving on to the lessons from the case study.

There are three important lessons to learn from ITC’s E-Cahupal initiative.

Number one,

technological accessibility, government regulation and cash-rich stakeholders are

the three pillars that can catalyse the growth of rural sectors of India.

In this case, the farm bill now legally allows companies to procure the produce directly

from the farmers without seeking special permission.

And thanks to Jio Kisan, farmers can now witness the next level of the E-Cahupal initiative.

Secondly,

we are seeing the rise of extremely cash-rich and not so profitable companies

like zomato and swiggy, who are building a b2b supply chain in order to supply raw materials

directly to the restaurants.

And just like ITC cannot own the supply chain, but only make it super efficient and profitable

both for themselves and for the farmers.

If this is done by the rest of the companies, the inefficiency caused by the APMC traders will

get eliminated resulting in huge profits to Grofers, zomato, swiggy, and other companies.

And lastly, most importantly,

if you’re someone who wants to invest in organic farming or

hydroponics please read about something called contract farming because it’s opening up new

supply chains that will eventually present you with game-changing business and investment

opportunities.